Lodging Facilities and Average Daily Rate

When appraising a lodging facility such as a motel, hotel, extended-stay hotel, campground, or destination resort one of the key issues an appraiser faces is determining the potential gross income within the Income Approach to valuation. A lodging property can offer a wide variety of room configurations, stay lengths, and payment options. One of the most common ways for an appraiser to calculate potential gross income is to calculate and an average daily rate for the property. In this blog, the difficulties of finding the potential gross income of a lodging facility and how to calculate average daily rate is discussed.

Lodging facilities are typically comprised of rooms with varying sizes and varying nightly rates. Additionally, rooms may be offered nightly, weekly, monthly, or some other duration of time. Rooms rented for longer durations offer a discount when compared to the nightly rate. Additionally, rates may vary depending on things such as purchase date or if the room was purchased through a discount website. Due to these factors, it can be difficult to estimate the potential gross income for a property, since the percentage of stays for each category (nightly, weekly and monthly) and the rates paid for each night can be difficult to track. However, calculating an average daily rate (or ADR) is an acceptable way within the lodging industry to channel all of the room income into one rate for analysis.

Average daily rate is “the average rate per occupied room”. The average daily rate for a lodging facility is calculated by dividing the total room revenue achieved during a specified period by the number of rooms sold during that same period. For example, I recently appraised a small destination resort property that offered one bedroom, two bedroom, and three bedroom configurations on a nightly, monthly, and weekly basis. Based on the different room configurations and lengths of stay, there was not an easy way to calculate the potential gross income for the subject’s rooms. However, the owner of the property provided us with their room revenue and occupancy rates by room type. From the occupancy rates we were able to calculate the total number of rooms sold, which allowed me to find the property’s average daily rate by dividing the total room revenue by the number of rooms sold. Finally, I was able to estimate the property’s yearly potential gross income by multiplying the average daily rate by the total number of rooms by 365 days.

Office Property Appraisal and the Proper Valuation Techniques, Part 3

In the third part of our look into the appraisal of office building properties, we will focus on some important issues related to the selection of comparable rental properties within the Income Approach. In order to have a reliable valuation, it is important to select comparable properties that could be substituted as an alternative to the subject property. Not every office space is the same and it is important for the appraiser to select comparable properties that are similar to the subject in terms of expense structure, quality, condition, and utility.

It is common to find office properties that are close to each other in proximity, but are not comparable to each other in any other way. For example, in downtown business districts of some metropolitan areas it is common to have several different types of office properties. One office property may consist of a recently completed Class A LEED-certified high-rise office building while another office property two blocks away may consist of a single-family residential home built in 1925 that was converted into an office building. Both of the properties are close in proximity but it would be unlikely that both properties could be used as comparables in the same valuation due to their differences.

Another important consideration when choosing comparable office properties is expense structure. The expense structure of a lease determines who is responsible to pay the real estate expenses, including the real estate taxes, insurance, management, utilities, janitorial, repairs and maintenance. It is possible that the lease may be on a full-service (gross) basis with the owner paying all the expenses related to the real estate, a NNN (triple-net) basis with the tenant responsible for all the expenses related to the real estate, or a modified-gross basis with tenant responsible for some expenses and the owner responsible for some expenses. If the subject property is currently leased, the best comparables would be properties with the same expense structure as the subject. Any differences in lease structure would have to be accounted for through expense adjustments.

If either of these issues is overlooked within the Income Approach, it could limit the reliability of the valuation. It is important that an appraiser consider all the factors that make up an office building market when selecting comparable rentals. If one factor is ignored, it could have a significant impact on the subject property’s valuation. For more explanation on appraisal methodology, visit our website at www.commercial-appraisers.com.

Office Property Appraisal and the Proper Valuation Techniques, Part 2

In the second part of our look into the appraisal of Office Building properties we will begin to take a look at some of the major issues to be addressed within the Income Approach of valuation. In the Income Approach, the appraiser needs to consider expense structure, appropriate procedure for predicting office rents, occupancy rate, and the proper method for choosing capitalization and discount rates. The first decision within the Income Approach the appraiser must consider is what type of analysis to use. Typically, either direct capitalization analysis or discounted cash flow analysis is used.

The direct capitalization method converts a single year's income or an average of several years’ income expectancy into an indication of value in one direct step by dividing the income estimate by the appropriate income rate, also called the direct capitalization rate. A capitalization rate ties property value to earning ability. Direct capitalization is suitable for properties unencumbered by leases; properties encumbered by short term leases; and/or properties encumbered by leases that reflect terms similar to the market.

In the discounted cash flow analysis, income and expenses are analyzed for each year of the projection or holding period, and the net income is discounted to the present value indication by applying an appropriate yield rate (discount factor). The value for the subject is estimated by summing the present values of cash flows during the projection period and the present value of the reversion at the end of the holding period (less typical sales costs). Discounted cash flow analysis is appropriate for properties with terms that differ from the market; erratic lease structures; or multi-tenant properties with a wide range in lease terms.

Typically, direct capitalization is appropriate for owner-user properties or smaller multi-tenant office properties while larger office properties typically require using a discounted cash flow analysis. Determining the correct analysis method within the Income Approach can make a significant impact in the final value of an office property. After determining the correct analysis method, the appraiser’s next step is to analyze extracted market income and expense data. In the next section of our look into the office property appraisal we will continue to look at some more issues an appraiser must address within the Income Approach.

Office Property Appraisal and the Proper Valuation Techniques, Part 1

When performing a real estate appraisal for an office property, the appraiser must first understand the theories, distinctive terminology, ideologies, and analytical methods associated with office building valuation. Distinctive emphasis should be given to the income capitalization approach and the intricacies of determining a value for properties with several tenants. The appraiser should be familiar with the attributes associated with the various styles of office buildings, significant inspection concerns, and industry measurement standards. This should be followed by a detailed investigation of the income approach by examining substitute lease types, appropriate procedures for predicting office rents, vacancy rates, and operating expenses, as well as suitable methods for choosing capitalization and discount rates. The appraiser should also consider the important concerns associated with the Cost Approach as well as the Sales Comparison Approach when undertaking an appraisal of an office building. In the first part of this series we will take a look at a major issue that should be addressed when using the Sales Comparison Approach in the valuation of an Office Building.

Generally, there are number of different types of office properties in a market; therefore, it is important to be thorough when researching comparable sales within the Sales Comparison Approach. For example, there could be two sales of office building properties that are of identical size. However, one of the buildings may contain an open build-out that is intended for a single user while the other building may contain heavy partitioning and be better suited for use as a multi-tenant property. If the appraiser was working on a real estate appraisal of an owner-user office property it would mostly likely not be appropriate to use the sale of a multi-tenant property that was fully leased at the time of the sale. An adjustment could be considered to account for the difference but it would be better to find sales that were also owner-user properties.

As seen in the previous example, the applicability of any individual valuation approach in an office building is usually a function of the current or intended use of the office building. The Sales Comparison Approach is the most applicable approach in the case of an owner-user office property while the Income Approach is the most applicable approach in the case of a multi-tenant office property. Generally, the Cost Approach would not be the most applicable valuation approach unless the property consists of a new building in an emerging market with limited comparable sales and comparable rental data. In the second installment of this series we will take a closer look the use of The Income Approach in the valuation of an office building.

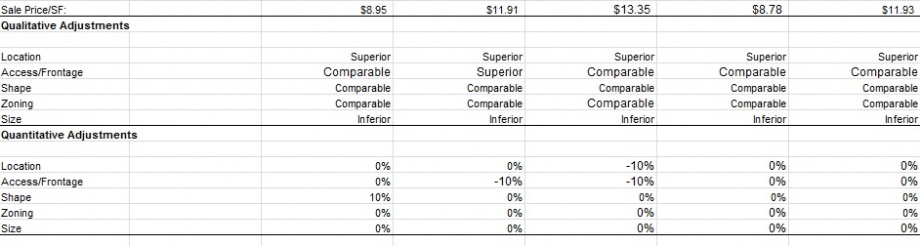

Quantitative vs. Qualitative Adjustments

Since two properties are usually not identical, especially in commercial real estate, it is essential for an appraiser to make adjustments within the Sales Comparison Approach. The adjustments made by the appraiser should imitate the market. For example, adjustments could include location, size, and topography for a property, if these are characteristics that the average buyer in the market would consider when making a purchase. Appraisers can use either quantitative or qualitative adjustments (or a combination of both). Generally, quantitative adjustments consist of making either percentage or dollar adjustments to account for the differences between the subject and the comparable sales. Qualitative adjustments require the appraiser to rank the comparable sales in terms of inferiority/superiority to the subject. Each of these techniques has its own weaknesses and strengths.

Quantitative adjustments are considered useful because they provide an actual quantifiable and measurable adjustment. Since the adjustment is quantified, it is more objective in nature than a qualitative adjustment. The result is a more scientific and precise analysis of the comparable data. However, the major weakness of the quantifiable adjustment is that it is rare to find the data to support quantitative adjustments. For example, the most common way to find a quantitative adjustment is to use a paired data analysis. In this analysis, two properties are compared two each other that are similar in all their attributes besides the one difference being analyzed. An example would be two lots that are identical except that one lot is a corner lot while the other is an interior lot. If the corner lot is $10,000 and the interior lot is $8,000, the appraiser could conclude a corner lot adjustment of $2,000, or 25%. The problem is that there is not typically enough data to provide paired sales for all the required adjustments for the subject property.

On the other hand, the biggest weakness of qualitative adjustments is that they are more subjective in nature because they do not include direct quantification. However, their biggest strength is that they match the typical behavior of most market participants. It is often more common for the typical buyer to compare property attributes on a scale of superior or inferior than to calculate market-derived adjustment factors. Both types of adjustments have their own strengths and weaknesses and when determining the applicability of using quantitative or qualitative adjustments the appraiser needs to consider the dependability of the market data in support of an adjustment and how market participants would make similar adjustments. Due to the imperfect nature of the real estate market, the judgment and experience of the appraiser is always a factor in determining what type of adjustments to use.

The Unfinished Office Park

Almost every larger town has one - the unfinished development project that was put to a halt during the economic recession. As the bottom fell out of the market, developers were caught with half-finished projects and a falling demand for commercial space. The result was a distressed property and an unusual appraisal project. Today’s post will take a look at an example of one way to approach the appraisal of a partially finished development project. The example focuses on using a retail sellout analysis to find the value of a partially completed office park development that includes two completed office buildings, two “shell” office buildings, and four pad sites for new construction.

The retail sellout analysis is a type of discounted cash flow where the retail values are determined through market research, and then discounted over an appropriate period, at a market-extracted discount rate. This process is crucial because of the time value of money, which is based on the premise that money currently in hand is more valuable than money in the future. The first step of the analysis is to determine the retail values of the subject property’s individual components. For the office park development example this step would include completing Sales Comparison and Income Approaches for each of the office buildings on an individual basis. In our example, this step may require the use of different comparables for the completed office buildings and the “shell” office buildings. (We will assume all the buildings are of similar size and construction) Additionally, the pad site’s retail values would need to be estimated using the Sales Comparison Approach. Since it would be difficult to determine which pad site would sell first, it is common to find the average price per pad site and use the average in the discounted sellout.

The next and often most difficult step, is to determine the most likely absorption of each of the developments components. This step requires a study of the subject’s market and research into the sellout of similar projects. In the office park example, we could conclude that either one pad site or one office building would sell per quarter indicating a sellout period of two years. After the absorption rate is determined, it is necessary to estimate the appropriate deductions for expenses such as sales costs, commissions, title insurance, D.O.C stamps, marketing/advertising, real estate taxes, etc. during the sellout period. The quarterly expenses would be deducted from the quarterly income.

Next, a discount (yield) rate would be extracted from the market. The final two steps would include discounting the net income stream for each period and adding the present values of the income stream for a total present value of the project. To complete our example, the present value of the eight quarters of the sellout period would be totaled to find the present market value of the subject office park.